Poka-yoke (ポカヨケ) is a Japanese term used at Toyota which means “mistake-proofing”. If you’ve never heard of it before, that’s okay. Not many people I know outside of Toyota actually heard of the term. It’s basically what we know as “foolproofing” (poka-yoke actually used to be called baka-yoke, baka meaning fool, but was deemed too offensive and was changed). But in every day life, you’ll come across poka-yoke without realizing it. Have you pressed the open button on your microwave while it was running and seen it shut off? You’ve just experienced poka-yoke. Instead of requiring you to manually turn off the microwave before opening the door, that safety switch corrected the power state so that you don’t have to be irradiated as a result of your “mistake”. If you’ve plugged something into the USB port, you’ve experienced poka-yoke. Notice how it’s impossible to plug it in the “wrong way”? That’s because it was *designed* to prevent you from putting it in the wrong way in the first place.

Background

Have you ever wondered why Japanese cars are known for their reliability? You can still see 20 year old Japanese cars happily chugging along with the latest and the greatest that the automotive world has to offer. It’s why they retain their values so well after all these years. Just go and look up used car prices for a 10 year old Toyota Camry vs Chevrolet Malibu. One of the key elements that brought success to Toyota as an automotive company in the 20th century was its disruptive manufacturing process called the Toyota Production System (TPS). Since then, Toyota has been renowned throughout the automotive world for its high quality, nearly indestructible vehicles and fairly low defect rates compared to other manufacturers. The TPS became precursor to many of the modern lean manufacturing processes used by other manufacturing industries today.

The Toyota Production System was developed by Taiichi Ohno and Eiji Toyoda between 1948 and 1975. It identifies and defines 7 kinds of waste (which they call “muda”) in manufacturing: overproduction, idle time, transportation, process itself, stock at hand, movement, and defects.

In the 1960s, a Toyota engineer by the name of Shigeo Shingo (新郷 重夫, 1909–1990) sought to eliminate the waste of defects. The defect he was trying to solve was a simple one: a switch button. He noticed that workers often forgot to install the required springs under the button which resulted in a defect. As a result, he redesigned the assembly process into a two step process: first, he would require the workers to prep the springs by placing them in the placeholder, then insert the springs into the switch. When a spring remained in the placeholder, workers knew about the mistake and correct it effortlessly before loading the next set of springs.

Shingo’s solution was a simple but an ingenious one. He recognized that human mistakes were inevitable and that mistakes were the causes of defects. Therefore, he concluded that it was much better to prevent mistakes from happening in the first place rather than fixing the defect down the line. He coined this solution as a poka-yoke.

Fixing broken things is a muda (waste)

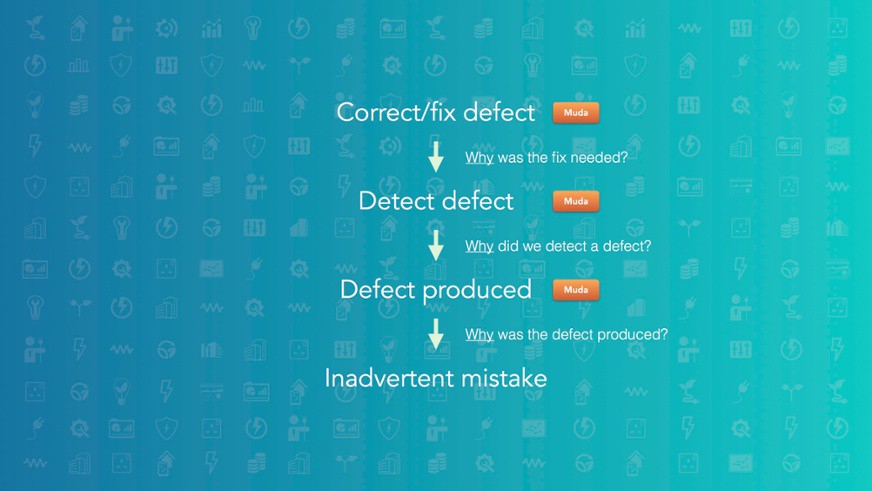

“From a lean process perspective, producing a defect, detecting it, and fixing it (or throwing it out) is unnecessary waste because there was no additional value produced by the fix.” If you think about it, you always start off with a good state. Then you inadvertantly make a mistake. It’s inevitable unless you’re a robot. And sometimes, the mistake will go unnoticed until it reaches the customer who complains about a defective product. You will then issue a recall, pay for shipping, take it apart, fix it, then you’re back to a known good state. From a lean process perspective, producing a defect, detecting it, and fixing it (or throwing it out) is unnecessary waste because there was no additional value produced by the fix. You’re back to square one after putting in all that extra effort.

To err is human

Once we accept that mistake *will happen* (it’s a question of *when* it will happen not *if* it will happen), we can identify areas where we can implement mistake proofing (a.k.a. poka-yoke). Identifying the source is often a process of asking a series of “why” questions.

Prevent mistakes at the source

Poka-yoke is essentially a process interlock and feedback mechanism to prevent mistakes and let the user know if mistakes have been made. If your product is hardware based, you can impose physical restrictions. Take advantage of square pegs and round holes; make it physically impossible for user to make mistakes.

Designing poka-yoke into your products

So how does this apply in design? It’s easier to just say build a product that prevent user mistakes but I believe it’s a lot more nuanced than that. Take one of the most common tasks we do on a web application: filling out forms. Let’s say we built a checkout form where the user could enter their billing information. If we didn’t have any poka-yoke, the system would not prevent the user from making mistakes. If they entered a typo in their credit card and phone number, it would happily store that mistake in the database and would go unnoticed until the system tried to process it and we tried to contact them by phone, only to realize the phone number was not really valid.

We could say that a poka-yoke is a form validation that rejects user submission if the input does not match the validation. But I don’t think this is enough. Mistake was still made. We only detected the mistake and told the user about it so they could correct it. What we want is to prevent mistakes at the source. For instance, use a filter to

Poka-yoke methods instead focuses on process innovations.

One thing that Toyota does very well is hammer the TPS methodologies to all its Team Members’ minds until they live and breathe Toyota’s processes. I still remember sitting through the new employee orientation learning about the pillars of Toyota Production System and how Kaizen, or the culture of continuous improvement, always pushes Team Members to think of new and innovating ways to improve processes. In fact, TPS itself was not invented overnight. It was a continuous reiteration and improvements of processes from late 1940’s with majority of the elements as we know it being implemented by the mid-70's.

Some of the key elements of TPS such as Kanban has been adopted outside of Toyota and has actually been incorporated into agile software development processes. Agile project management tools such as JIRA, Trello, Pivotal, etc. are basically digitalized, electronic versions of a 60 year old idea that disrupted manufacturing logistics and enabled Just-In-Time manufacturing.